• Oil & Gas,Pipeline Operators

• Oil & Gas,Pipeline Operators

There is a quiet revolution underway in the way pipeline operators protect their assets, their neighbors, and their reputations. It does not involve laying new pipe, redesigning SCADA systems, or adding headcount to field inspection crews. It involves looking down — from orbit — and letting algorithms see what human eyes and traditional sensors routinely miss.

The economics of pipeline incidents are unforgiving. Between 2010 and 2024, the United States recorded more than 9,300 pipeline incidents (roughly 1.7 per day), resulting in nearly $9 billion in cumulative property damage, 183 fatalities, and the evacuation of more than 51,000 people. In North Dakota alone, 113 incidents over a recent 12-year period released more than 2.2 million gallons of hazardous liquids.

The financial toll of a single event can be staggering. When a North Dakota pipeline company allowed 29 million gallons of produced water to flow unchecked for 143 days — contaminating land, groundwater, and over 30 miles of Missouri River tributaries — the result was $35 million in criminal fines and civil penalties, plus untold remediation costs. Even small spills carry disproportionate expense: documented cleanup costs have run as high as $5,000 per gallon for minor releases, driven by mobilization, specialized equipment, and regulatory response requirements that don't scale down just because the spill volume does.

These numbers make an essential point: in pipeline integrity, the cost of not knowing dwarfs the cost of knowing.

One of the most compelling demonstrations of geospatial analytics at work in pipeline monitoring has been unfolding across North Dakota's Williston Basin, where the operators produce over 1.2 million barrels of oil per day and tens of thousands of miles of gathering lines thread across remote prairie terrain.

In 2022, a leading oil and gas operator with extensive assets in North Dakota suffered a devastating equipment failure. Over the course of nearly a month, approximately 34,000 barrels of produced water leaked from a pipeline onto surrounding farmland before the release was detected. The cleanup costs, regulatory fines, and erosion of landowner trust that followed served as a watershed moment. The operator resolved that no leak of that magnitude would ever again go unnoticed on its watch.

The company was already familiar with satellite-based monitoring through its participation in the intelligent Pipeline Integrity Program (iPIPE), a pioneering consortium created in 2018 after North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum challenged the industry to end pipeline leaks through innovation. iPIPE brought together major operators to test and advance emerging detection technologies, from golf ball-sized inline inspection tools to satellite-based, AI-powered analytics. The consortium earned the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission's Environmental Stewardship Award for its collaborative approach.

By October 2022, the operator contracted for weekly satellite-based monitoring across its entire North Dakota footprint — pipelines, well pads, and compressor stations alike. More than three years later, the program continues and has expanded under new ownership following the company's acquisition by a global energy major.

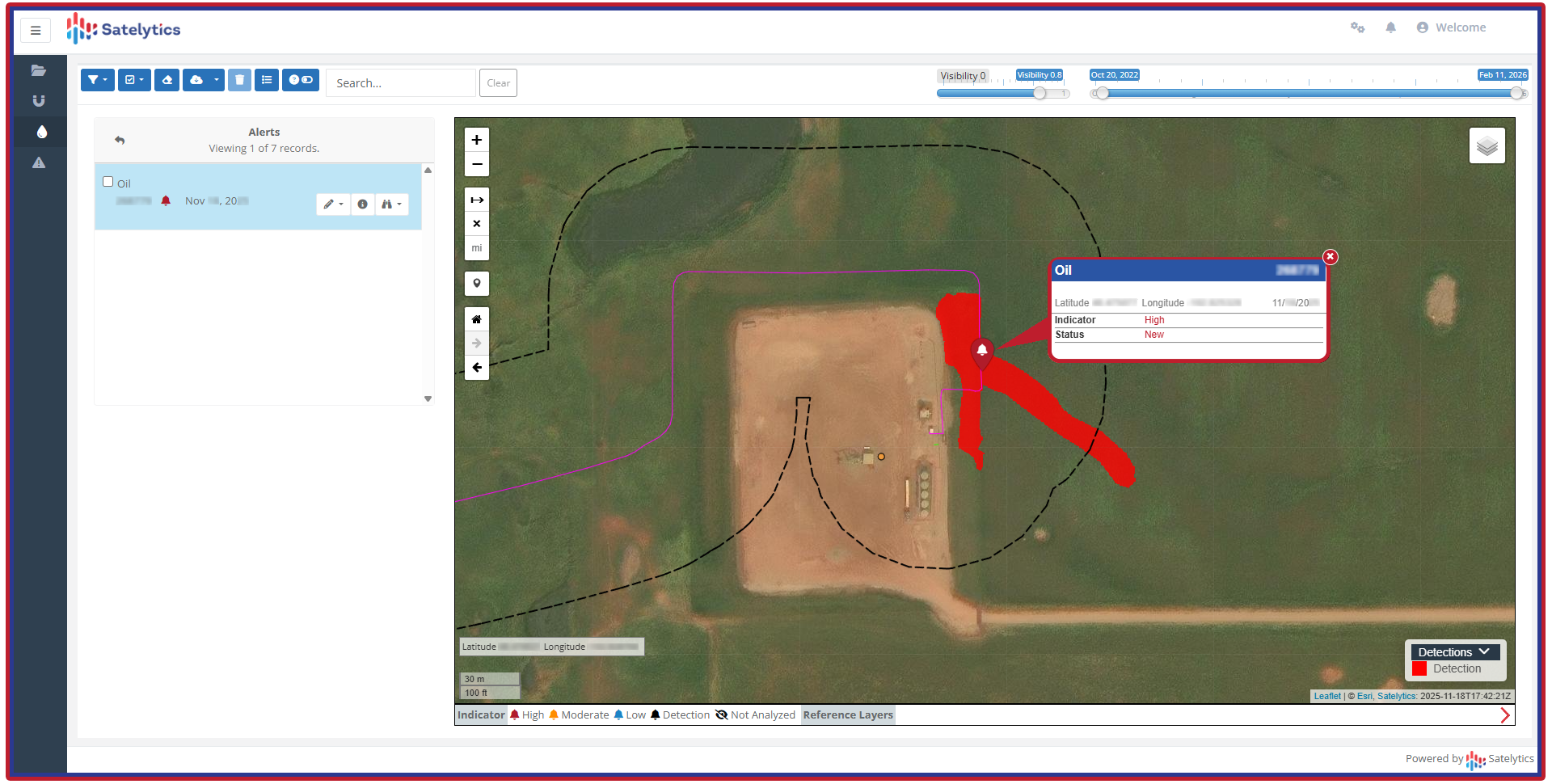

Crude oil gathering pipeline leak.

The results speak to the transformative potential of routine geospatial surveillance. Since launch, the monitoring program has identified dozens of confirmed crude oil and produced water leaks at their earliest stages, often before field crews, SCADA alarms, or routine inspections flagged anything at all. Several of these early detections have been documented in leak reports filed with the North Dakota Department of Environmental Quality's HazConnect database, with Satelytics specifically cited as the initial detection agent.

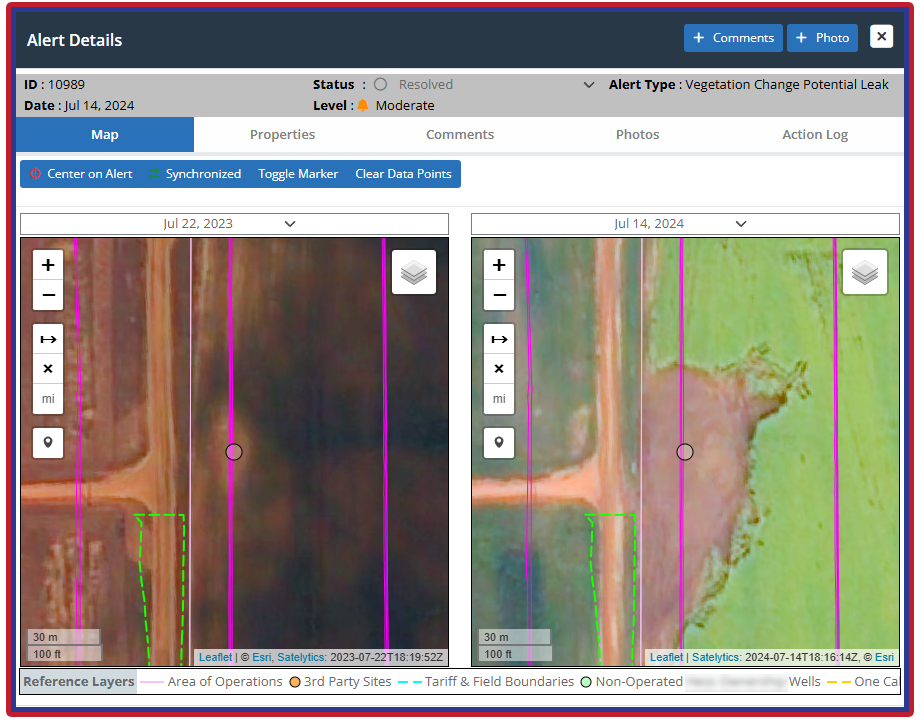

But perhaps the most unexpected outcome has been the identification of gas leaks through an indirect pathway. In ten documented cases, satellite-derived vegetation stress analysis detected changes in plant health that signaled underlying gas releases — fugitive emissions that would have otherwise gone entirely unnoticed by conventional means. This finding underscores a broader truth about geospatial analytics: the same technology that detects liquid on the surface can simultaneously monitor vegetation health, land movement, surface disturbances, erosion, and third-party encroachments that threaten pipeline rights-of-way. A single platform, a single weekly cadence, multiple threat categories addressed.

Hidden gas leak discovered by failing vegetation.

The program has also deployed coarse-resolution methane measurement capabilities, giving the operator an independent, privately managed tool for gauging large-scale methane emissions. This information also serves as a valuable check against both internal inventories and the methodologies published by external non-governmental organizations.

The broader industry context makes this case study particularly relevant. The global market for satellite-based pipeline monitoring reached $1.28 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow at a 9.4% compound annual rate through 2033, driven by the increasing complexity of pipeline networks, tightening environmental regulations, and the practical impossibility of patrolling thousands of miles of remote gathering lines with boots on the ground alone.

At the same time, the regulatory environment continues to evolve. While the EPA's Waste Emissions Charge for methane was repealed under the Congressional Review Act in early 2025, the underlying methane reporting requirements and New Source Performance Standards (NSPS OOOOb/OOOOc) remain on the books, with compliance deadlines extended but not eliminated. Operators who build monitoring capability proactively position themselves ahead of whatever regulatory posture ultimately takes hold, yielding a far more defensible strategy than scrambling to comply after the fact.

What the North Dakota experience illustrates is not merely a technological curiosity but a strategic posture. Weekly, basin-wide geospatial monitoring transforms leak detection from a reactive scramble into a managed, proactive discipline. It converts unpredictable catastrophic risk into a steady stream of actionable intelligence. It produces a documented, auditable record of environmental vigilance that strengthens relationships with regulators, landowners, and the public. And it accomplishes all of this at a fraction of the cost a single undetected major spill would impose.

The operator that pioneered this approach in the Williston Basin was not chasing a regulatory mandate. It was responding to a hard lesson, and then building something far more durable than a compliance checkbox. Three years in, with dozens of early-stage detections confirmed and a program that has survived a corporate acquisition and is being evaluated for expansion, the evidence is clear: the satellites are not just watching. They are finding what no one else could.

For operators managing gathering systems across remote basins, the question is no longer whether geospatial analytics can work. It is whether you can afford to operate without them.