• General

• General

Satelytics has always maintained a strict philosophy regarding data acquisition: we are platform-agnostic. Whether the pixels come from a drone flying at 200 feet, a fixed-wing aircraft at 3,000 feet, or a satellite orbiting at 300 miles, our AI-powered algorithms remain indifferent. We simply ingest the imagery, hunt for spectral signatures (be it methane leaks, vegetation encroachment, or mineral deposits), and deliver the answers you need.

However, being platform-agnostic does not mean we are blind to operational reality.

As we move through 2026, our customers in the energy and utility sectors are facing a new and difficult truth. While the capability of drone technology remains impressive, the viability of deploying drone fleets for large-scale infrastructure monitoring is colliding with a "perfect storm" of regulatory, economic, and logistical headwinds.

For operational leaders managing thousands of miles of transmission lines or sprawling upstream assets, the question is no longer "Can a drone do this?" It is "Can we afford the friction of doing this with drones?" The data from 2026 suggests that for large-scale operations, the answer is increasingly "no."

The most immediate shock to the system has been the fallout from the FCC’s foreign drone ban, enacted in late 2025. For years, the commercial drone ecosystem was built on affordable, high-performance hardware, primarily from DJI. With the "Covered List" designation now fully in effect, that ecosystem has been upended.

While existing fleets were grandfathered in, they are living on borrowed time. As batteries degrade and airframes wear out, operators are finding that replacement costs have doubled or tripled. The domestic manufacturing base, while growing, has not yet achieved the scale necessary to offer price parity. Furthermore, the battery supply chain crisis, exacerbated by restrictions on Chinese-manufactured components, has left even compliant "Blue UAS" manufacturers struggling to fill orders.

For a utility company planning a vegetation management budget, this introduces unacceptable volatility. You cannot build a five-year predictive maintenance program on hardware that might cost 300% more next quarter or be unavailable entirely.

Perhaps the most persistent misconception in our industry is the idea that drone operations are "automated." The reality is that "unmanned" aerial vehicles are incredibly labor-intensive.

Regulatory promises regarding Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations have largely stalled in a swamp of red tape. The FAA’s Part 108 rules, while a step forward, have introduced complex compliance burdens that favor massive logistics companies over utility operators. For most operational environments, you still need a pilot. Often, you need a visual observer. You need a vehicle to get them to the remote access road. You need insurance, which has seen premiums spike as underwriters react to the new "SAFER SKIES" Act and the increased risk of drone interdiction near critical infrastructure.

Consider the logistics of monitoring 500 miles of electrical transmission corridor for vegetation encroachment. Using drones requires a rolling convoy of trucks, charging stations, and certified crews moving stop-and-go along the right-of-way. It is not an automated data stream; it is a construction project.

Even if you can afford the hardware and find the crews, you face a physical constraint that no regulation can fix: the "Data Gravity" problem.

Drones equipped with the high-fidelity multispectral or hyperspectral sensors required for Satelytics’ advanced analysis generate terabytes of data every day. In the remote environments where our energy sector midstream customers operate — West Texas, the Canadian oil sands, the Australian outback — high-speed internet is a fantasy.

We have seen too many customers trapped in the "Sneaker-Net" cycle: drones capture critical data, but that data sits on hard drives in the back of a truck for days until the crew returns to headquarters to upload it. By the time the imagery reaches the Satelytics cloud for processing, the "real-time" insight is already stale. A produced water leak detected a week late is a liability, not an asset.

Produced water leak detection.

Ultimately, the friction of drone operations comes down to a mismatch of scale. Drones are tactical tools; infrastructure is strategic.

If you need to inspect a single flare stack or a specific substation transformer, a drone is the perfect tool. But if you need to monitor vegetation health across a three-state transmission corridor, the drone is the wrong instrument. It is like trying to paint a highway with a toothbrush.

Weather dependencies further compound this mismatch. As we’ve seen this year, flyability rates for commercial drones in key regions can drop below 50% due to wind, precipitation, and temperature extremes. When you manage critical infrastructure, you cannot tell your stakeholders that safety monitoring is paused because it’s too breezy.

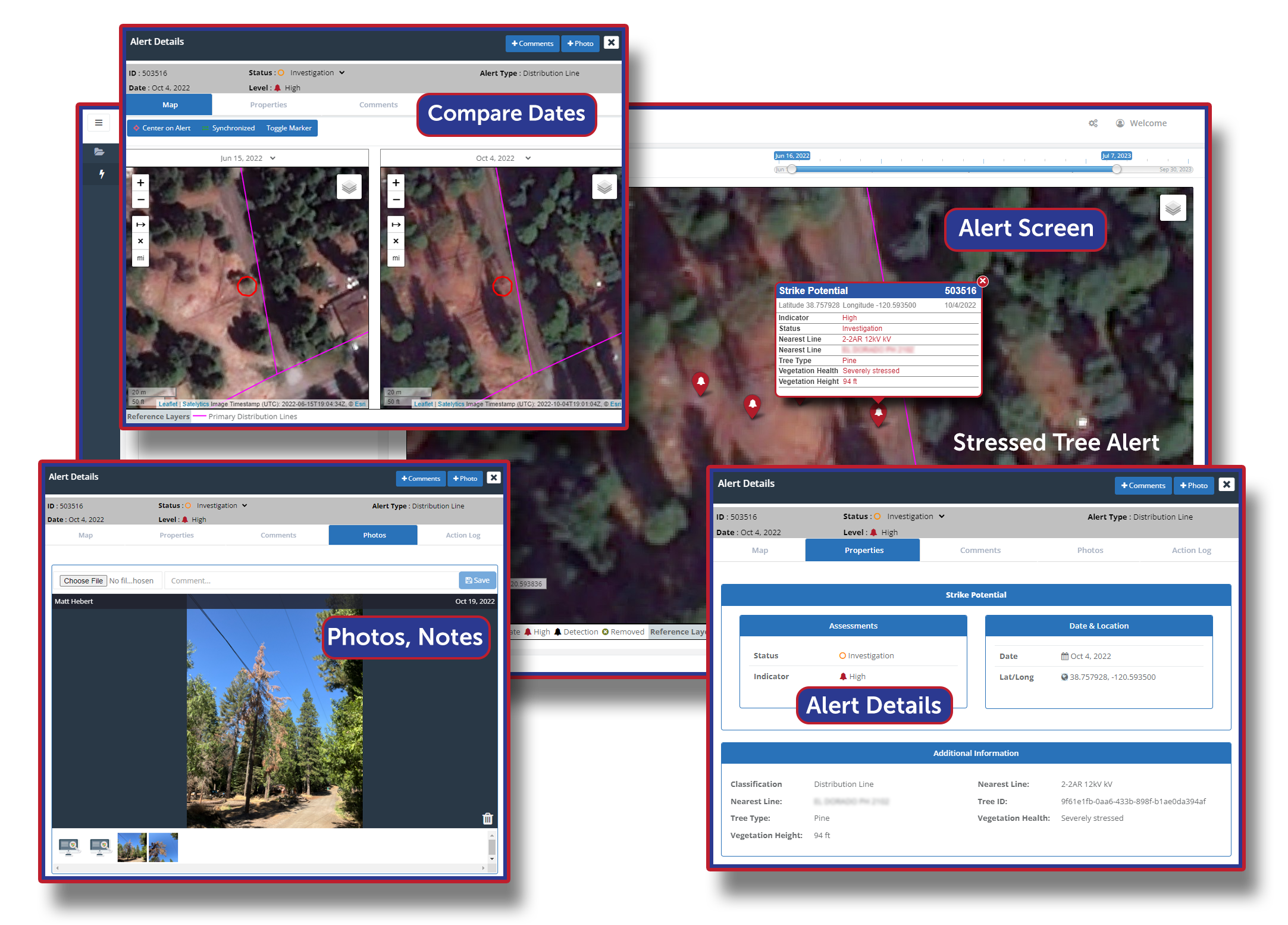

Vegetation risks alerted before catastrophic harm results.

This is where the conversation shifts. While Satelytics remains agnostic, we increasingly advise our enterprise customers to look up. Way up.

The commercial satellite constellation in 2026 has matured into a reliable, high-frequency, global monitoring infrastructure. The headwinds battering the drone industry simply do not exist in orbit.

Satelytics’ capability to detect small, but meaningful changes is only as good as the image we receive.

In 2026, the operational cost of acquiring that image via drone is rising, while the reliability of acquiring it via satellite is stabilizing, and the cost of the satellite imagery is declining. For our customers in vegetation management, methane measurement, and change detection, the path of least resistance is becoming clear.

We will always accept your drone data if it meets minimum standards. But we invite you to ask yourself: Do you want to be in the business of managing aviation logistics, navigating federal lawsuits, and hunting for batteries? Or do you want to be in the business of answers?

The headwinds against drones are strong and growing. Fortunately, at 300 miles up, the view is clear.